The History of the Reaching Children’s Potential Program from Anse-la-Raye to Ipalamwa

Running to catch a taxi after meetings at the World Food Programme (WFP) in Rome, Nancy Walters, a senior executive at WFP, handed me a copy of The Essential Package and encouraged me to read it. This United Nations agencies document detailed 12 interventions recommended for developing country governments to improve the well-being of primary school children. I read The Essential Package on the flight from Rome to Minneapolis. That changed everything!

By Bud Philbrook, Co-founder & CEO

It was the fall of 2010, when I sent the list of 12 interventions to our staff around the world, asking them which, if any, of them our community partners had asked for help. The response was quite interesting. Although we were not doing more than three or four of the interventions in any one community, we were engaged in 11 of the 12 somewhere.

The following winter, I traveled to five continents to meet with community partners and show them the list of 12 interventions. After discussing with each partner the community projects they had asked for assistance, and informing them that we were doing 11 of the 12 interventions in one country or another, I asked if there were others on the list for which they would like help. The response was unanimous. Every community partner wanted assistance with all 12.

Offering vital interventions to primary school children so they can learn better is a necessary and helpful objective; however, it is not sufficient because it lacks scope. The research literature clearly stated that the first 1,000 days of life are the most important time for all human beings, and conducting interventions when children are already five or older is too late to impact many children’s futures. So, we researched which of the 12 would be most effective for pregnant women and their young babes. We quickly discovered that each intervention prescribed by the UN agencies could help improve the health and well-being of mothers and their infants and toddlers.

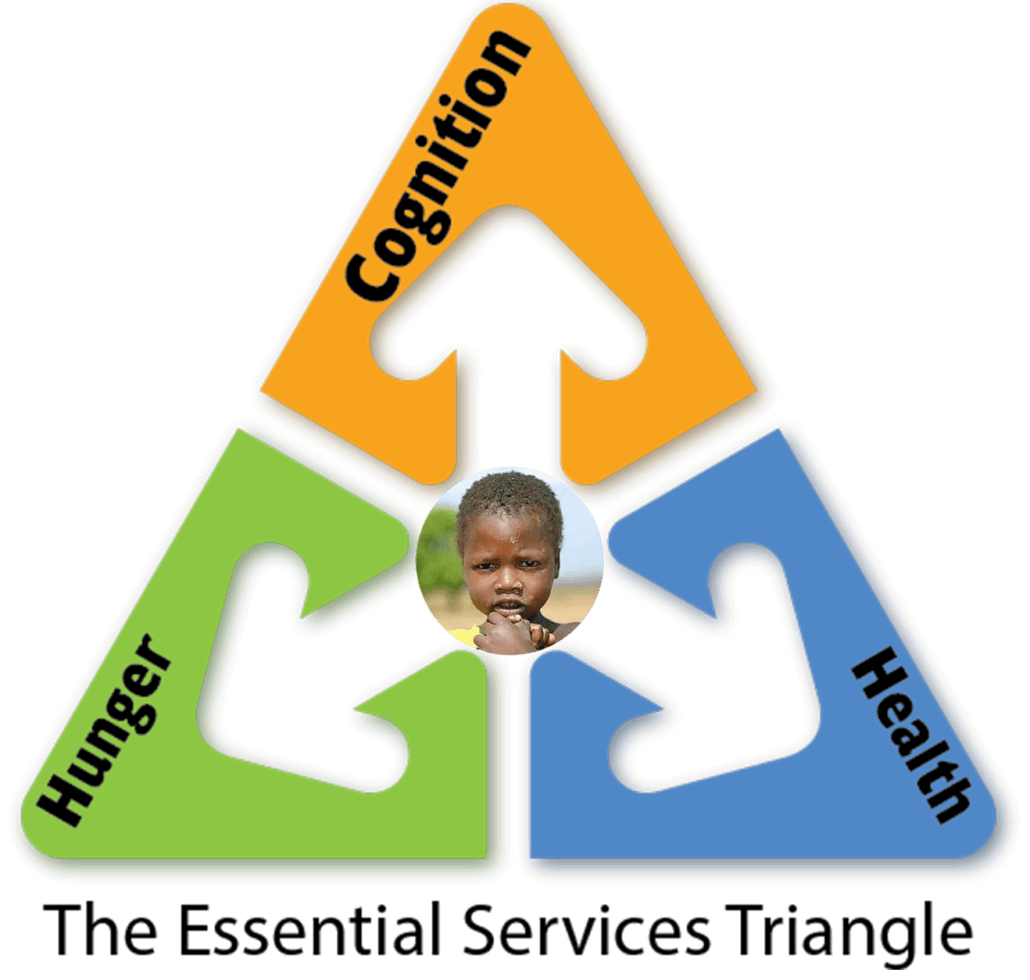

Global Volunteers published “The Essential Services” in 2011, a substantive prospectus extracted from “The Essential Package,” focusing on the needs of pregnant women, infants, and toddlers. We grouped the 12 Essential Services into three primary categories of Hunger, Health, and Cognition.

HUNGER

1. School and household gardens

2. Child Nutrition

3. Micronutrient supplementation

4. Improved stoves

HEALTH

5. Health, nutrition, and hygiene education

6. Malaria and Dengue fever prevention

7. De-worming

8. HIV/AIDS education

COGNITION

9. General education

10. Promoting girls’ education

11. Potable water and sanitation facilities

12. Psychosocial support.

These evidence-based services ensure sufficient nutrition, prevent disease, provide education, and enable parents to guarantee their children can reach their potential. For each of the 12 services, the prospectus described activities in which short-term volunteers could be engaged and encouraged the reader to invest their time, skills, and money in the future of the world’s children.

So as not to clutter the research value of this effort, we solicited an invitation to offer the 12 Essential Services from a country in which we were not currently working. Bill Westbrook, a retired advertising executive who offered his expertise pro bono, suggested we start in St. Lucia after reading an article in the Economist about the tremendous needs there. The following May, Ron Reimann, a member of Global Volunteers Board of Directors, and I traveled to St. Lucia on an exploratory trip. There, we met Father Athanase Joseph, a Catholic priest at the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary Catholic Church in the seaside community of Anse-la-Raye. After several lengthy conversations, he invited us to engage volunteers at the parish “Infant School” (kindergarten through second grade), and “Kids Step Preschool” (for children aged one year to five). Father Joseph also introduced us to community leaders at the primary school and community organizations who also invited us to send volunteers. In January 2012, the first team of 24 volunteers and Warren Williams, one of our longtime volunteer team leaders, and me functioning as co-team leaders served in Anse le Raye St. Lucia.

One of the Anse-la-Raye community organizations was the Roving Caregivers Program (RCP), a Caribbean-based local government-funded early childhood development intervention to help mothers improve their children’s lives. A primary component of this program was weekly home visits conducted by RCP staff. They requested our volunteer professionals to accompany their staff on home visits to potentially enrich the conversations with the mothers. We quickly learned that volunteers greatly enjoyed this assignment, and the mothers were pleased as well.

Unfortunately, the St. Lucia government decided to defund the RCP program, which served multiple communities across the island. However, the government agreed to allow Global Volunteers to take over the program in Anse le Raye. Because the name “Roving Caregivers Program” was the intellectual property of the Caribbean organization, we renamed our effort. Throughout the community, this program was known simply as “RCP,” so we chose a name that continued to reflect that acronym. Hu Di, Global Volunteers, Director of International Operations responsible for Saint Lucia, proposed “Reaching Children’s Potential” (RCP).

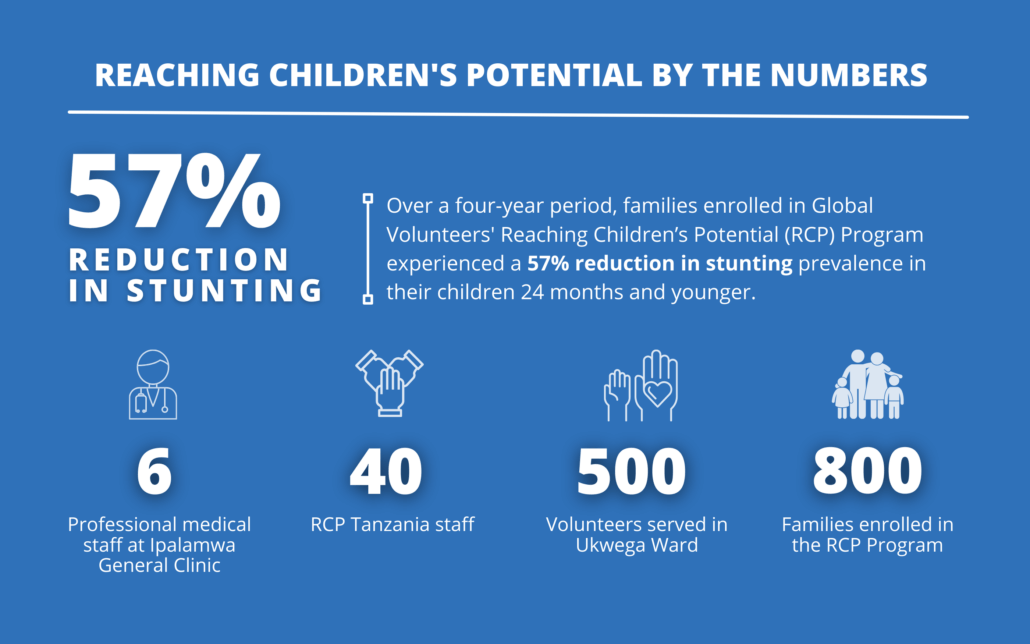

After three-plus years and engaging 490 short-term volunteers, we wondered what measurable contribution the volunteers were making. To answer this question, Global Volunteers commissioned a research team comprised of three Masters of Development Practice students from the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota to assess how the use of foreign volunteers affected the delivery and outcomes of services provided by the RCP program. The purpose of the evaluation was to help us better understand how RCP program participants viewed the use of foreign volunteers, the distribution of Earthboxes, and the parent educational workshops so we could use the information for programming decisions and improvement.

After six weeks on the island, the three graduate students and their faculty advisor reported that the mothers found the volunteers’ involvement extremely beneficial. The parents noted that their children’s interactions with volunteers helped their cognitive development, and they appreciated the training received in early childhood development from the volunteers. Many moms valued the workshop lessons in sanitation and hygiene, nutritional awareness, child safety, and child rights, and they spoke about how the workshops used effective and creative methods of communicating including audio-visual media. Most mothers also wanted additional Earthboxes to help them grow more vegetables, thereby minimizing market purchases.

Sadly, in addition to defunding the Roving Caregivers Program, the St. Lucia government also failed to accommodate or even minimally encourage our efforts to continue the RCP Program. Consequently, based on the Humphrey School research and the positive responses from the mothers and our volunteers, we decided to conduct the RCP Program somewhere else. Global Volunteers informed community partners around the world that we were looking for another community to offer the 12 Essential Services.

Tanzania Bishop Owdenberg Mdegella, with whom we had worked since 1987, immediately responded that he and village leaders in the Iringa region wanted to benefit from the RCP Program. After conversations with him about the serious challenges of working in a country where the government was not supportive, the bishop introduced me to the Tanzania Prime Minister and then the president of Tanzania. After a meeting in the presidential office, President Kikwete invited Global Volunteers to conduct the Reaching Children’s Potential Program in the Iringa region, working in partnership with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania. Bishop Mdegella proposed we start in Ipalamwa, his home village. He assured us that the families there needed the program and would welcome Global Volunteers into their community.

In February 2017, Ipalamwa community members broke ground for the first building in the RCP Center. Because we had engaged short-term volunteers in Tanzania for 30 years, we knew we needed a comfortable guesthouse to recruit enough volunteers to conduct the program. With money from a very generous donor, we constructed a 12-unit double occupancy facility with private baths, hot water, 24/7 electricity, and a spectacular view from the veranda. Later, with money from other very generous donors, we constructed a full kitchen, a dining hall that also serves as a learning center for parent workshops, a modern health clinic, a greenhouse to produce seedlings for Earthboxes, comfortable staff housing to encourage Tanzania professionals to move from the cities to a remote village, and a storage facility – a total of nine structures.

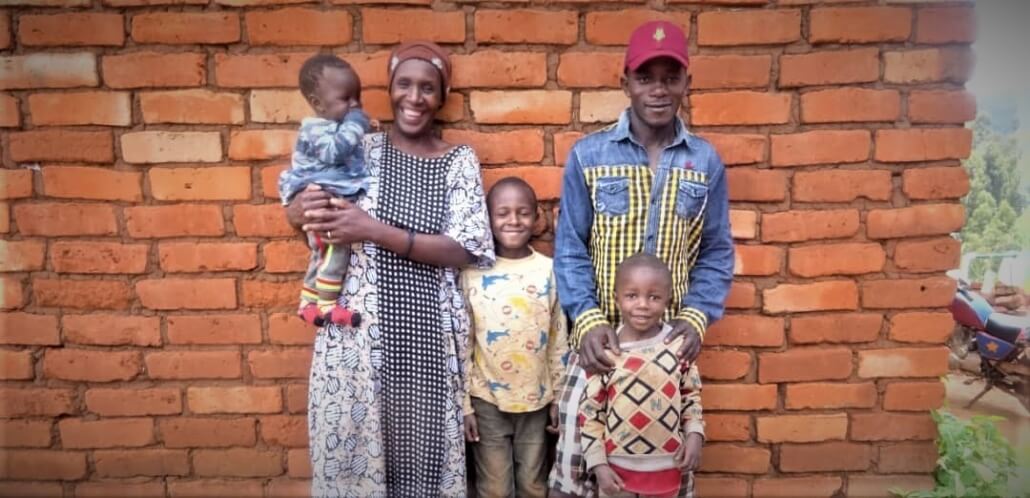

In the spring of 2017, we hired four Tanzanian women professionals as the initial caregivers to enroll families in the program, conduct weekly home visits, help facilitate workshops, and guide volunteers. Before the first team of 16 volunteers served in July of that year, the caregivers had enrolled 50 families in the RCP Program. Under the direction of local leaders, these volunteers presented parent workshops, participated in home visits, and conducted a health survey.

After initiating the RCP Program in Ipalamwa, other village leaders from the surrounding area asked Global Volunteers to replicate the program in their communities. Lulindi, Mkalanga, Ukwega, and Makungu, along with Ipalamwa, comprise the Ukwega Ward, and within a few years, we had accepted the invitations from each of these villages.

Today, more than 900 Tanzania families are enrolled in the RCP Program in the Ukwega Ward. In addition to six medical professionals employed by the ELCT, 40 Global Volunteers employees manage and facilitate the RCP Program in this area. Under the leadership of Nayman Chavalla, Global Volunteers Tanzania Country Director, and a management team of five Tanzanian women professionals, two of whom are from the original four caregivers hired in 2017, the families in these villages have achieved remarkable improvements in the health and well-being of their children, reducing the prevalence of childhood stunting by 57%. Now we intend to replicate and scale the RCP Program in every community that invites us so that all Tanzania parents, every African family, and all people around the world can ensure their children can reach their potential.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!