Global Volunteers “Conceived” on Honeymoon

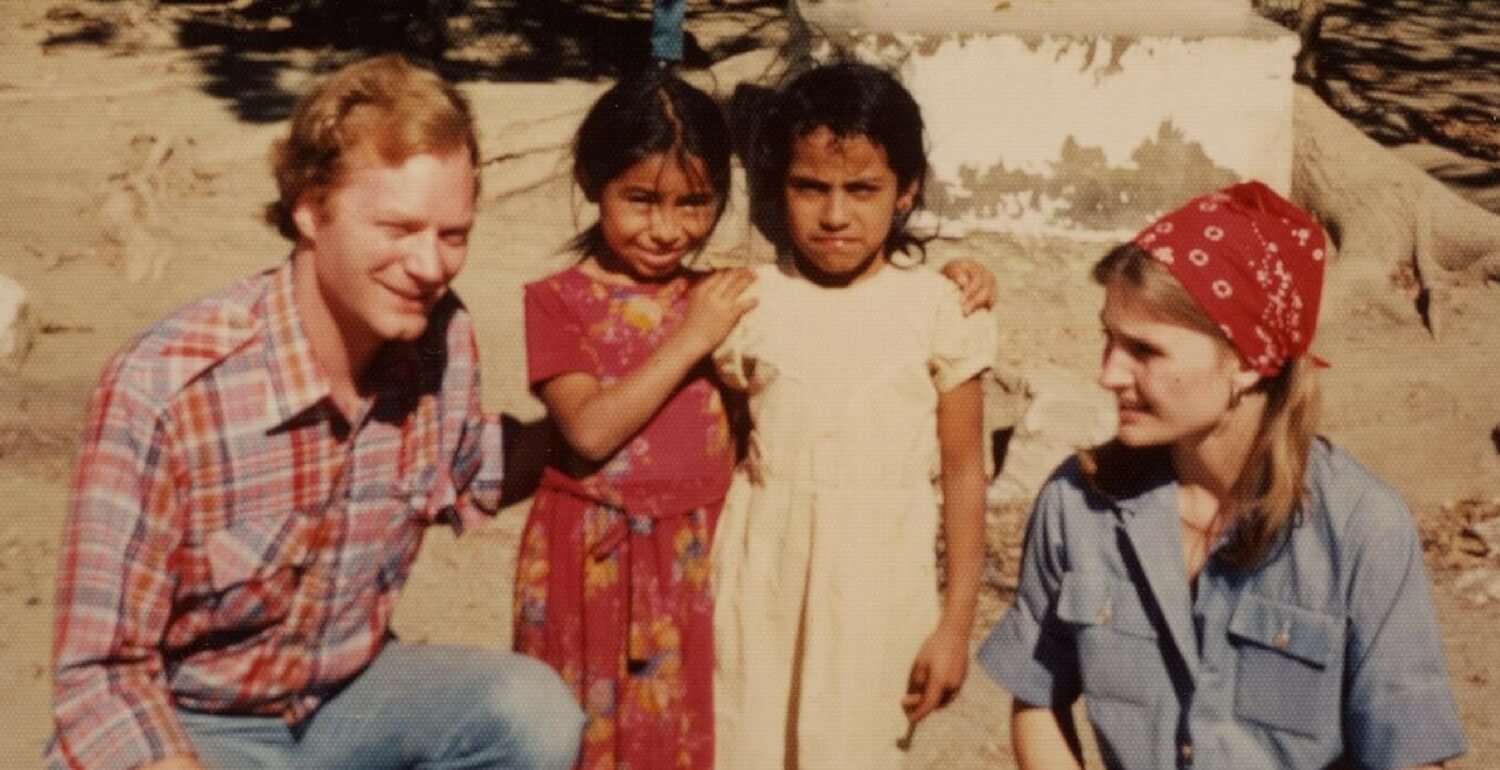

Michele Gran and Bud Philbrook’s unconventional honeymoon led to Global Volunteers’ founding in 1984. That year, the Jamaica Service Program began with two teams. Since 1984, we’ve worked in more than 200 other communities worldwide. Global Volunteers’ honeymoon story is told here by Co-founder Michele Gran, who is pictured below holding a child in Jamaica:

Our Honeymoon of Purpose

Occasionally in life, you get to do something amazing. What’s more, you might change your life forever, and find yourself on the Oprah Winfrey Show! (Watch video here: https://globalvolunteers.org/global-volunteers-on-oprah-show/)

In January 1980, we enjoyed what my husband, Bud Philbrook, wryly refers to as “a properly balanced honeymoon.” We spent five days indulging Bud’s childhood dream to visit Orlando theme parks, followed by five days in an impoverished Guatemalan village. This curious blending of Disney World and “the real world” eventually led to a life change that involves thousands of others around the world.

Originally, our honeymoon plans centered around a “barefoot cruise” in the Caribbean. But it was late in 1979, the period of a massive exodus of Hmong and Cambodian people into the vast waters toward America. Week after week, evening network newscasts spotlighted the growing tragedy – the casualties of capsized refugee boats lost in the frigid waters. A cruise seemed increasingly frivolous to us within the context of world events. We decided to create a more meaningful vacation for ourselves, where we could experiment with being true “world citizens, ” – if only for a short time. We thought perhaps we could contribute our skills to an international organization that needed help. But where would we find such an outlet?

We Offered Ourselves as Volunteers

We contacted an international development organization we supported and explained our idea. They were less than encouraging at first. Having only limited experience with church groups and student volunteers, the program directors were skeptical about our practical value to their village projects. But, persistence won out, and they eventually agreed to a five-day visit at one of their more established sites in Central America. Aware that their acquiescence was less an acknowledgment of our usefulness and more a cautious indulgence of our idealism, we earnestly accepted our invitation to Conacaste, Guatemala. Four months later, as newlyweds, we were off on our honeymoon!

After a predictably captivating week in Florida, I was both eager for, and apprehensive about the next leg of our journey. The evening before our flight, I mentally reviewed all I knew about Guatemala. It took about two minutes. On the plane, I mentally replayed news stories while my idealism melted into acute anxiety. I shut my eyes tight to hold back the tears. Descending to the airport, I prayed that I could be useful in some small way. I had never before, nor since, felt so inadequate.

Our introduction to Conacaste assuaged my fears. The program directors and local community leaders, several of whom spoke English, welcomed us warmly. One of my first thoughts were: “They’re just like us!” Gazing around the gently folding valley, a sense of purpose overcame me. My comfort grew each time a nodding or smiling villager greeted me or waved in my direction.

Our Honeymoon Village

The little mountain hamlet housed some 200 families, descendants of indigenous Indian tribes. They welcomed us into their homes, fields, and friendly conversations. I was awe-struck by how utterly normal – albeit difficult – life there seemed. With minimal electricity, no running water — except in the community center — few books, no organized children’s activities, and no stores for daily necessities, the villagers accepted their challenges not with resignation, but with determination. I enjoyed the easy spirit that guided village life.

There was also something distinctly celebrative about the village. I noticed the colors first: From the brilliantly flowering bushes and trees in every yard, to the gleaming pastel clay-brick houses with doors and windows outlined in vibrant reds, greens and blue designs.

In the streets, black-haired women and girls wore intricately-patterned woven skirts and shawls and carried brightly decorated pots and water pitchers. Men and boys guided livestock harnessed with ropes dyed red and yellow. I was mesmerized by the natural beauty around me.

As I grew more accustomed to my temporary “home, ” the local residents became more familiar. I was grateful for their acceptance –me, a gringo woman. The children were especially engaging. Frisky as pups, and immune to their humble surroundings, they swarmed around us, ever-ready for a game of “toss.” Soon, it was on to our work assignments. Bud, with his background in human and economic development, was asked to help write a grant proposal, and I, with my journalism background, began work on a brochure explaining the community’s needs to potential benefactors.

Each morning, I was jolted awake by the abrupt hawking and scratching of the roosters perched on our tin-roofed room. Exotic birds peered curiously at us through the screened window as the interrupted moths scattered. Before daybreak, I strained to hear the distant chortle of the gas-powered corn grinder in the tortilla “factory” in a next-door family’s shed: “Putt-putt-putt- hiss-hiss-putt-putt-his…chuncka-chuncka..” It amazed me how quicly these sounds became familiar. Soon after, the village animals started their wake-up routine – bleating, howling and shrieking their discordant choir – and I giggled at the utter goofiness of it all. Only as the earliest fingers of the sun’s ochre rays stretched tentatively into the village lanes did low human voices become audible. Soon, sunlight illuminated the eastern fields, and every living creature in the village was engaged in the new day.

A short distance away from the eight-by-ten-foot concrete room in the community center that served as our guestroom, the village’s sole typewriter awaited my day’s efforts. The ever-present dogs and numerous village children gleefully followed me on my ten-minute walk down one of the main paths. We passed the open doors of several village businesses – efforts to help the local people achieve self-reliance. There was a bread-baking “industry, ” which had begun the previous year by a group of village women. Together with project leaders, the women built a central brick oven and baked dozens of loaves each day which were sold to village families and occasional visitors.

A basket-weaving center was being constructed with the financial assistance of grants and individual contributions, and the labor of student volunteers. The project leaders explained that progress was slow, because as a demonstration project, the construction techniques used must be replicable with locally available resources. The American program directors knew that the initiative, as well as the strategies, must be the local people’s themselves, if the community’s efforts would remain in the long-term. Therefore, construction practices that to me had first seemed awkward and unnecessarily labor-intensive, gained greater relevance as I began to understand the meaning of “appropriate technology.”

Dispatching my “escorts” upon arrival at my destination took longer than the walk itself! But returning their toothy smiles and indulging their youthful games warmed me with a peace I can still recall today. Five days passed much too quickly.

Each afternoon, as I walked by the open doors of the villager’s homes — with the hard-packed dirt floors and peevish front-yard chickens — I tried to imagine the tiny village in 20 years. Would one-room, thatched-roofed homes be replaced by more spacious, or at least substantial dwellings? Would educational and medical facilities be built to ensure the children’s health and development? Would farmers develop agricultural techniques to raise the families’ subsistence-style of life? I at once felt called to try to make a difference.

Leaving Our Mark on the World

Less than five years later, we had indeed begun to help the people of Conacaste. And we didn’t stop with just one village. Now, more than three decades later, I have personally witnessed what is possible when local initiative and community self-determination joins with catalytic assistance from committed “outsiders.” Global Volunteers exists to enable local people to enlist others’ support and practical skills to visualize and achieve their community hopes and dreams. Along the way, as we work together, we learn we are much more alike than different, an understanding that is foundational to achieving respect and world peace.

With our Conacaste honeymoon as a springboard, Bud and I worked with like-minded friends and associates to establish a non-profit organization that would wage peace through person-to-person development assistance in host communities around the world. In January 1984, a board of directors was established and Global Volunteers was founded. Bud led our only two volunteer service programs that year to Woburn Lawn, Jamaica, a “sister village” of Conacaste. The North American project directors in Woburn Lawn were “alumni” of the Conacaste project through the same development organization. The next year, we began sending short-term volunteer teams to Conacaste to complete the circle.

Our short-term volunteer “experiment” has subsequently been welcomed in more than 200 host communities in some 35 countries on six continents. While our partnerships have changed over the years, our commitment to providing meaningful volunteer opportunities by working toward local human empowerment has remained constant. Lives have been forever altered – those of the volunteers, and of the people they have so generously served. Like most people, Global Volunteers’ team members are at first motivated to make a difference, to “give back” some of what they are grateful for in their own lives, and to know that in a small, personal way, they have altered the course of world history in a positive way. It is upon reflection they often realize — perhaps as they are packing their bags to return home — that they are the ones who have truly benefited from their act of service. Life will never be the same. They have their own story to tell. Now, that’s amazing!”