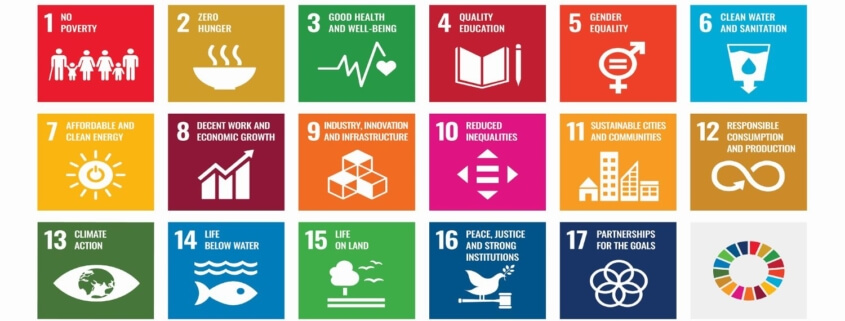

Operation Bootstrap Africa and the Sustainable Development Goals

In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a “shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future” to be achieve by 2030. The SDGs were preceded by the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which directed the world’s governments and development institutions toward equality in meeting the world’s needs. Global Volunteers is committed to the vision and volition of the SDGs, and the MDGs before them, and measures our outcomes accordingly. In this blog series, we share the work of companion organizations toward achieving the SDGs. Read on for an interview with Operation Bootstrap Africa Executive Director Jason Bergmann.

When Operation Bootstrap Africa (OBA) was founded in Minneapolis in 1965 by Lutheran missionary Rev. J. David Simonson, a “bootstrap” philosophy guided his vision. Living with his young family among the Maasai people of Tanzania had taught Rev. Simonson that no person can pick themselves up by their own bootstraps. But, with appropriate assistance, people can help themselves.

With two U.S. staff and a passionate board of directors, OBA strives to create opportunities and empower people in Tanzania, Madagascar and Kenya to advance their own lives and communities through improved access to education, healthcare and sustainable agriculture.

Prominent in Jason’s mind is not only what OBA does to address the SDGs, but perhaps more importantly, how they meet those global goals.

“We always ask, what’s the impact of Western influence in the communities,” Jason explains. Their model is to sponsor and support existing African organizations serving impoverished people by engaging a broad and diverse donor base of largely U.S. individuals. They focus largely on services for women – the primary change-agents on the continent. “We don’t have our set goals; our (community) partners come to us to define what their goals are,” Jason said. “We partner with them to strengthen their capabilities. They have smart, talented hard-working people, and don’t need me to tell them what to do.”

Too often, he continued, developing communities become overrun by NGOs. “They end up destroying the local culture and the economy, (because) “they’re clueless to either the bigger picture or the cultural picture, or the effects.” OBA is careful to target assistance where it’ll have the greatest impact, without treading on local norms, traditions or plans, all the while maintaining checks and balances within the administration of the program.

Education is the Key Component

Jason offers their Arusha nursing program, established six years ago, as an example. In that time, they graduated three classes. “With a 100% pass rate on our equivalent to the ‘Bar exam,'” he adds proudly. There’s a great nursing shortage in Tanzania, he explains, with 5,000 patient to each nurse. Compounding the shortage is the type of training offered through government schools. “They teach how to take blood pressure and how to give injections, and the like,” he says. “But they don’t teach, or even encourage compassion. And so when you train a nurse, you’re creating a strong professional person.”

The Arusha Lutheran Medical Center identified the need for a nursing school. “We walked alongside them and said we’d like to help with tuition subsidies. The cost to train a nurse at the school is about $1,800, so we subsidize $1,000 per student and require the student pay the balance to have skin in the game.”

It’s not easy to balance community needs such as this with donors’ concepts for solutions, Jason admits. That’s the challenge of what he calls “good development.”

“We want to give (local people) the tools that they need to create the change they want in their country without us dictating, because we don’t know, we don’t have the answers. We might think we do sometimes, but we certainly can’t predict the outcomes.”

For instance, organizations that do for people, instead of engaging them fully are likely to fail. “An organization was punching holes in the ground for wells, because you know, water is very important in the bush,” Jason recalled. “But the wells weren’t running, and when I asked why, they said, ‘we ran out of fuel.’ And, sometimes they’d break down, and they didn’t have money to fix them. As you know, good development requires community input. That’s not what they were doing.”

By contrast, he said, OBA prefers simple technology that local people can understand and manage on their own. “This is what I bring to our board. They’re smart and accomplished individuals, but they may not have a knowledge of international development.” For example, he references an OBA scholarship program in Madagascar to enable community leaders to travel to Kenya to learn about constructing sand dams in dry land environments.

“It’s a beautiful mechanism, where you slow a river down during the rainy season, and you create a sediment trap. The (constructed) dam captures soil-laden water behind it. Forty percent of the sand behind the dam sinks to the bottom, and what remains is a clear and pure water source. And it’s not subject to mosquitoes or other pathogens and bacteria you might have problems with. And, it restores the aquifer.”

He also points to an agricultural school teaching sustainable farming such as terracing and fish farming when appropriate.

“So, we find that a lot of it revolves around education; and so then how do we support our African brothers and sisters to do that, to learn and do that work themselves? Education really is the key.” OBA focuses largely on girls’ education. “This is what we teach donors. Because, if you want to create change in the village, you work with the women. And, I don’t need to tell you that if a woman has a couple of extra bucks, it’s going back into the family.”

A Focus on Girls and Women

Jason offered another story. “Last year in January, I took a group of donors to Tanzania for the 25th anniversary of the Masai Girls’ School. I identified some of the girls from the original graduating class, and I asked to talk to them.” Of those who were willing to talk, there was an architect, a medical doctor, a pilot, a social worker, a graphic designer and one woman who decided to return to her traditional village life. “The goals of the school, from the very beginning,” he continued, “was to just give these girls a little better education, give them an opportunity to expand their horizons, and postpone marriage and babies. By giving these girls a job they have an independent life. They have self-direction and are empowered. They’re not necessarily strictly dependent upon a man in their life.”

Two days later, he was at the airport and returning to Minnesota with his donor group. “And somebody comes running up and says ‘director, director,’ and I started looking around, and I see it’s her – the traditional village girl. I asked what she was doing there. She said: ‘Oh, I’ve been asked to speak at a symposium at Oxford University in London.’ Amazing, right? Well, I think there we have impact on many of the SDGs in that one short story.”

Perhaps the greatest challenge of the organization’s international philanthropy is negotiating appropriate expectations for donors and local leaders. As a charitable organization, OBA strives for transparency and accountability. To this end, Jason explained that donors always accompany him on overseas partner visits so they can see first-hand how their gifts are used.

The Donor’s Dance

“Our donors are great people, and when they start developing a relationship with somebody in Africa, they want to help. But, as successful Americans, they’re used to a very fast pace, and that means they oftentimes can carry on their own agenda. That’s where I have to have a plan. I tell them that during our local visits, they can observe from the back of the room. And sometimes we sit under an Acacia tree and it takes a long time. We’re there to listen and I never designate an agenda. They’re not always patient enough to understand the intricacies of international development. So even though we could leave a school with without a plan for next steps, I know that I can come back and remind them what we talked about. Again, most of our work is in education. It may not be in the actual construction of brick and mortar schools, and we’re not necessarily putting in wells, and we don’t have a need for back hoes, specifically. That’s the challenge.

To address donors’ desire to have a more direct relationship with the sponsored students, Jason described a private online chat system to facilitate donor/student communications. “The sponsor can login through our website, and send a message to the student, and the student will get notified when they login through our website.” Jason then has the opportunity to discuss with the donor any concerns or requests that come up through this communications channel “to help put it into the correct cultural context.” The goal is to cultivate realistic expectations on both sides of the equation. “Once (donors) have this understanding, they continue and embrace it. And I believe (local leaders) know that I value their culture and them as individuals. I’m trying to walk shoulder to shoulder, you know?”

The Delicate Balance Shifts and Adapts

OBA prefers long-term projects, but is realistic about crisis conditions that require stop-gap responses. Jason said the global pandemic has put already struggling communities into even greater need. He hopes the outcome won’t be short-term relief that can make donors feel better, but cause long-term damage. “I did grad work in 2000 in Kenya and Tanzania. And Kenya had over a thousand NGO’s at that point. I looked, first of all at all their clothing drives, you know, ‘we’re going to give money to the naked kids in Africa.’ But that destroyed their local textile industry… all of these seemingly, really good intentions have a lot of consequences.”

He described one OBA school program in an urban area that relies on tourism. “There are 1,500 children there who come at 7 in the morning and go home at three o’clock in the afternoon, very much like our schools. There’s no food or water on campus. And because it’s an urban school, supper is not assumed. Often, they get only one meal a day. There’s no place for their parents to grow food. So we set up this program where the parents paid for the cooking and the firewood, matches, and things like that. And we paid for the groceries, about $14 per child daily. The parents’ part is one-third and ours is two-thirds. But because of the pandemic, and absence of tourists, families are trying to live without income. So now we’re paying the parent’s portion as well, and for the short-term we evaluate every month.”

In Love With The African People

“I feel like I’m plugging into something that’s greater than myself,” said Jason. “I studied philosophy and theology, psychology and anthropology, but there’s something about our work that is greater than ego, it’s greater than finance, it’s greater than most of the motivations that humanity operates under. I’m in love with the people and I can walk with them and maybe make things a little bit easier for them.” He said he liberally shares this personal passion with donors in a cautionary way.

“Our donor groups come in from all over the US, and we all meet in Amsterdam. There, I give them a warning. I say, ‘this is your last chance, because I’m going to tell you this. By entering that airplane, your life on the planet will never be the same.’ There’s something about Africa that enters your soul, and you can’t give it up.”

While the work OBA does is tangible, the outcomes transcend measurements, Jason asserts. In that regard, the SDGs are more a guide than a prescription. “I’m very, very fortunate to be standing on the shoulders of my predecessors, who did such amazing, solid work, and the founder – 50 years ago – understood this,” Jason concluded. “The Sustainable Development Goals are really good, because they help focus our attention on good development. And you do it with some trust and a power greater than yourself, I think.”

Global Volunteers respects and supports Operation Bootstrap Africa’s work to bring the benefit of the SDGs to struggling communities in Africa. We share their vision to help achieve well-being for all without compromising the potential of future generations to meet their needs, and invite opportunities for NGO partnerships in these areas. Read on to learn how Global Volunteers’ impacts address the United Nations SDGs and how our Reaching Children’s Potential Program is helping to end stunting in Tanzanian villages.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!