The Hunger Project and The Sustainable Development Goals

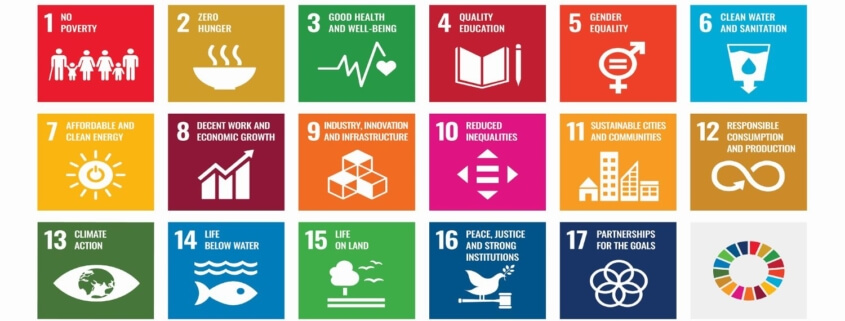

In 2015, the United Nations adopted 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a “shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future” to be achieve by 2030. The SDGs were preceded by the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which directed the world’s governments and development institutions toward equality in meeting the world’s needs. Global Volunteers is committed to the vision and volition of the SDGs, and the MDGs before them, and measures our outcomes accordingly. In this blog series, we share the work of companion organizations toward achieving the SDGs. In this post, we present The Hunger Project (THP) in an interview with Vice President John Coonrod.

The Hunger Project’s stated mission is to end hunger and poverty by pioneering sustainable, grassroots, women-centered strategies and advocating for their widespread adoption in countries throughout the world. So we started our interview by talking about what causes hunger and why women are at the center of the solution.

“Hunger is a natural consequence of a system of inter-related stakeholders,” John explained. As such, it’s a silent, invisible symptom of poverty, and is exacerbated by a host of socioeconomic causes.

“We recognized early on, that hunger wasn’t quote, ‘an issue.’ Hunger is at the nexus of a whole range of issues from women’s rights to food security, to nutrition education, to water and sanitation, and access to health care.”

Ending hunger requires a systems restructuring, he said. “Governments support siloed, top-down, short-term projects that are never sustainable.” So, a “package of integrated goals” was THP’s rubric for the systems change attacking the root of hunger. “We’re all about local leadership, local civil society and strengthening local government, to achieve a comprehensive set of goals,” John expanded.

Improving on the Millennium Development Goals

To understand how THP activates these systems changes in working toward the SDGs, the outcomes of the preceding MDGs provide a perspective.

“There was no community focus whatsoever for the MDGs,” John said. “They looked so aspirational and, frankly, they didn’t look attainable early on. Governments in developing countries were running top-down programs, rather than the way it works in rich countries, which is where the services are delivered at the community level, the ward level, the municipal level. So we pressed hard to get that in the development of the SDGs. I was lobbying for these multi-sectoral or local strategies and I wasn’t alone. Because they needed to focus on sustainability and as it turns out, sustainability is a community-level attribute. We lobbied hard at the international level, in the run-up to the MDGs, and then again, in the run-up to the SDGs, for there to be an integrated package of goals.”

And, how did the focus center on women’s roles for THP’s contribution to the SDGs in Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America?

“The World Bank’s research demonstrated that if you seriously wanted to reduce childhood stunting and wasting, you would really need a multi-sectoral strategy to address nutrition, and to focus on adolescent girls and moms, and that that leads to this understanding that child nutrition is based primarily on maternal nutrition.”

“Nutrition really was the first big, multi-sectoral strategy in the world because it said, you know, for moms to (be healthy) they had to have clean water. And, they had to have delayed age of marriage, delayed first pregnancy, access to health care, and affordable nutritious food.

Further, they had to address gender discrimination. “You know, little girls were taught to eat last and least – after the men and boys ate.” It was clear that girls’ and women’s roles in society had to be addressed simultaneously with other more visible inequalities leading to hunger.

Women’s economic empowerment also rallied NGOs together. “There were lots of studies showing that moms are the caregivers, the farmers, and the processors. They have to do everything. And unless women have reliable access to a comprehensive set of public services, they’ll never escape extreme poverty.”

Pulling it all Together in an Agenda to End Hunger

John said the response had to be a “women-centered strategy,” because “women are doing most of the work, and they’re getting no voice in the decisions that affect their lives.”

Not long after developing their model, THP concluded that the deeply patriarchal structure of society needed to be transformed. “We noticed our own women-centered programs were nice, but, in some ways, they were really just a very sophisticated band-aid because the real root problem was that the gender-related discrimination was underlying hunger and poverty in every single region.”

So, in India, they taught women to become politically organized, to establish their own federations, develop their own leadership and “really be linked powerfully with the next level up.”

Newly empowered women, serving as role models for girls in their villages, laid a foundation for girls’ rights. “There were no women’s rights to speak of, but everybody loved their daughters,” John elaborated.

“In Africa, our pathway was educational, financial and economic empowerment. In Africa, women’s society is almost like a parallel society to men, socially, but they lack access to financial services. So, we combined our bottom-up strategies with strategies that were intentionally gender-transformative. But, it was pointed out to us that anytime you created a parallel structure to government, which is what a lot of NGOs do, you are undermining democracy. So we promised that everything THP would henceforth do would either be in partnership with local government, or if local government wasn’t working, it would be devoted to fixing local government.”

Local organizing takes the form of block-level federations of 100 or more women meeting together to share goals and an agenda. “They empower each other and lobby the leaders at the next level, but what was critical was having that kind of collective voice and not just one or two women.”

John explained that as these locally-elected women leaders eventually obtain an equal voice in higher levels of government, they became instrumental in large-scale change. “If you create an environment in which men and women can think through this for themselves, and you really hold them to it, you know, it’s transformational,” he asserted.

Measuring Local Outcomes With an International Scale

“Every single day, we use the framework of the SDGs as the framework for thinking about how communities end their own hunger,” John explained. “At least 12 of the SDGs require integrated local solutions. And so we definitely have communities track their progress, on their goals, within the SDG framework. But the national level indicators are usually statistically based and aren’t particularly relevant to communities, so there’s some alignment with SDG indicators, and some not.”

He demonstrated the computer program that organizes data from epicenters – local governing bodies which plan and track their goals and outcomes. “The epicenters have subcommittees to work on specific needs. For instance, the epicenter may negotiate with the district government and traditional chief to assign a nurse midwife to the epicenter.” If the strategy is aligned with both traditional and district power authorities, it’s likely to be accepted he said. THP developed an epicenter toolkit to help advance this model worldwide.

“You know, from our perspective, the importance of all those goals is communities setting targets and achieving them,” John reflected. “All of our strategies are designed to enable communities to really successfully take charge of their own development, to be self- reliant for their own development, so they don’t need charitable inputs to make further progress.”

In 2011, THP won a grant from the UN Democracy Fund to develop a process for participatory local democracy and set up a Washington DC advocacy office to drive the project.

Three years later, after conducting a number of conferences, they designed a Movement for Community-Led Development, a coalition of civil society and governments that address five goals:

- Voice and agency for women, youth and all marginalized groups

- Adequate community finance

- Good local governance

- Quality public services

- Resilience in disaster preparedness and risk-reduction.

CLD chapters in turn catalyze change by sharing strategies, developing a research agenda and nurturing CLD champions to bring CLD to scale.

It’s this perpetual bubbling up of new concepts – new systems – that keeps John motivated in his work to fight hunger. In his childhood, he “wanted to change the world.” The culture of the ‘70s, made that goal seem possible. THP was the vehicle and his source of inspiration since then. “What keeps me going is the participation of the people in the communities. Seeing the amazing change in people give me a great deal of satisfaction,” he reported. “And, working with our investors. They’re motivated by breakthroughs. In-person trips and virtual community visits. Monthly webinars. Anything that can bring them into the heart of the work.”

Global Volunteers respects and supports The Hunger Project’s work to bring the benefit of the SDGs to struggling communities around the world. We share their vision to help achieve well-being for all without compromising the potential of future generations to meet their needs, and invite opportunities for NGO partnerships in these areas. Read on to learn how Global Volunteers’ impacts address the United Nations SDGs and how our Reaching Children’s Potential Program is helping to end stunting in Tanzanian villages.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!